AI and Cognitive Over-the-Counter Transhumanism

How Consumer AI and ChatGPT Tech Blur the Line Between Tool and Self

Introduction

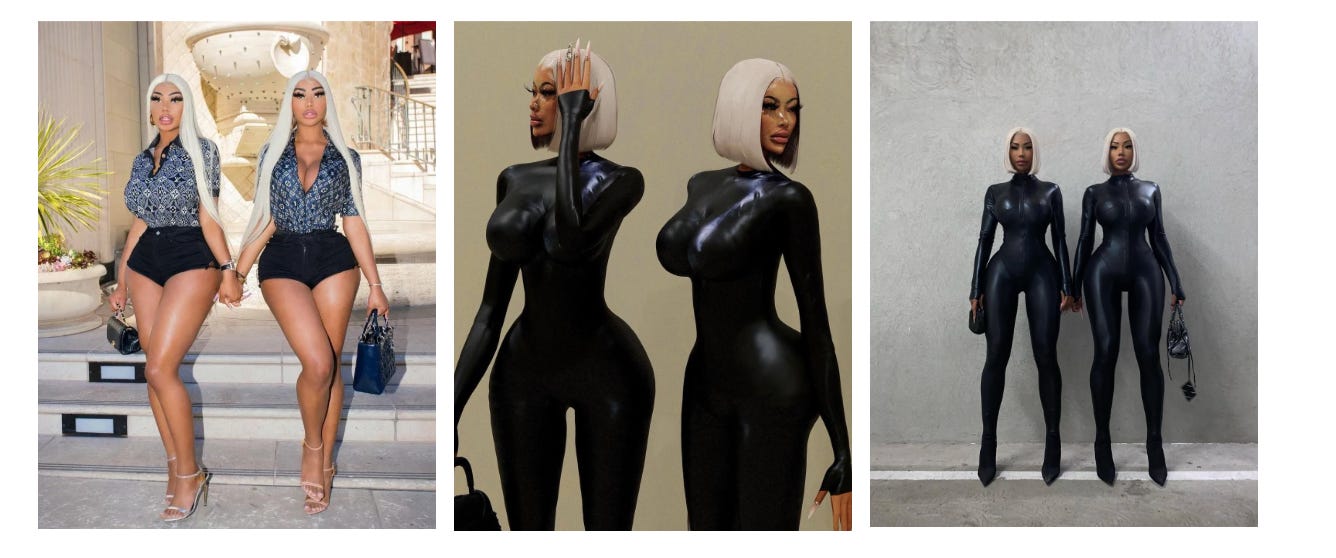

The Brazilian butt lift (“BBL”) has become a mainstream obsession. In perfect algorithmic, addictive brainrot fashion, I was watching a TikTok where the creator mentioned that BBLs are a form of transhumanism. The creator argued that individuals have a perceived self, which they embody through physical means, and by augmentation, someone can reach their desired “avatar.”

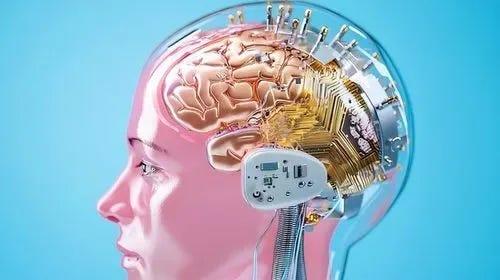

This creator’s offhand remark shows how readily people embrace technology-driven self-modification in everyday life. Such cultural anecdotes hint at a broader phenomenon: an emerging form of “over-the-counter” transhumanism. By over-the-counter, I mean enhancements that are accessible without specialized clinics or implanted devices, practically consumer-grade boosts to human abilities. Notably, these enhancements are increasingly cognitive rather than physical. Just as social media filters and cosmetic procedures allow “one-touch magic” to reshape our appearance, AI tools like ChatGPT offer on-demand augmentation of memory, creativity, and problem-solving.

We’ve been doing it for ages, from writing and printing to smartphones and search engines, each innovation profoundly changing not just how we live but even who we are. But ChatGPT’s arrival in late 2022 felt different in scale and immediacy. Suddenly, a powerful AI, capable of answering questions, writing code, brainstorming ideas, and more, was in the public’s hands. At this pace, the question is no longer whether sustained ChatGPT use makes us a little bit transhuman; it’s whether the tool is now so deeply embedded in that threshold that it verges on pseudo-cyborg technology.

Defining Transhumanism

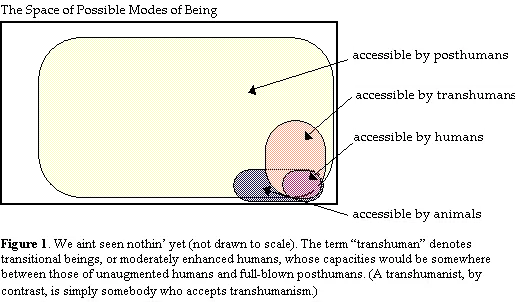

To ground the discussion, let’s start with a clear definition of transhumanism. In simple terms, transhumanism is the concept of utilizing advanced technology to surpass the natural limitations of the human organism. Transhumanism is described as a movement that advocates using current or emerging tech such as genetic engineering, cryonics, AI, nanotech, etc. In other words, transhumanists want to transcend the normal human state through science and tech, eventually maybe even becoming “posthuman” beings with expanded capacities that an unenhanced human wouldn’t possess, thus enhancing human capabilities to improve the human well-being.

Modern theorists in the transhumanist school of thought offer complementary definitions. Philosopher Max More who helped formalize transhumanist thought in the 1990s, defined it as “a class of philosophies that seek to guide us towards a posthuman condition”. He emphasized that transhumanism shares humanism’s respect for reason and science but “differs from humanism in recognizing and anticipating the radical alterations in the nature and possibilities of our lives” resulting from advancing technologies. Along the same vein, former Oxford futurist Nick Bostrom explains that transhumanists see human nature as “a work-in-progress, a half-baked beginning”. We need not accept our current mental and physical limits as the endpoint of evolution. With “the responsible use of science, technology, and other rational means,” Bostrom says, transhumanists hope humans will “eventually manage to become posthuman, beings with vastly greater capacities than present human beings have”. Yet these ambitions have also drawn sharp criticism. Skeptics argue that the movement’s rhetoric can hide an elitist desire to engineer a “better” class of humans, stoking fears of selective biological enhancement and widening social divides.

In his 2004 Foreign Policy essay “Transhumanism,” Stanford political scientist and author Francis Fukuyama warns, “If we start transforming ourselves into something superior, what rights will these enhanced creatures claim, and what rights will they possess when compared to those left behind?”

In short, transhumanism is about deliberately using technology to overcome our biological limits, whether it longer lifespans, enhanced bodies, or sharper minds. For the fiction nerds, picture the Mentats in Dune, those human “living computers” trained to perform the feats once handled by banned thinking machines.

ChatGPT and the advent of chatbots

At first glance, a chatbot on your computer or phone might not sound as dramatic as cyborg implants or designer genes. After all, ChatGPT doesn’t physically change your physiology rather it’s “just” a very smart tool. Yet the threshold between general tool and a true transhumanist enhancement isn’t always clear-cut.

Transhumanism isn’t limited to physical upgrades. Enhancing cognitive abilities is equally central, and many prominent transhumanists actively pursue it. Just as we accept eyeglasses and prosthetic limbs as bodily augmentations, we can likewise regard an AI assistant as an augmentation for the mind. The key distinction is whether the tool merely offers convenience or if it genuinely expands what we can know or do as humans. A simple calculator, for example, is very useful but arguably just automates a narrow mental task. ChatGPT, by contrast, can generate new ideas, text, and solutions. Such cognitive interactions can converse, explain, and create in ways that feel like having a second brain on call. When a technology begins to so vastly amplify one’s intellectual output or understanding, it starts to cross into the transhumanist realm of qualitatively enhanced capability. ChatGPT, in essence, allows a person to tap into a vast web of knowledge and a reasoning engine adjacent to any individual’s mind. That is why some have described it as a form of cognitive enhancement available to the masses, an “over-the-counter” cognitive boost that doesn’t require a PhD or a billionaire budget to use.

With the right user-driven guardrails in place such as prompt engineering, ChatGPT pushes beyond the ordinary tool threshold of transhumanism and emerges more as a cognitive steroid.

The Extended Mind

Long before AI chatbots, philosophers were already arguing that tools can become literal extensions of our minds. In a famous 1998 paper titled “The Extended Mind,” Andy Clark and David Chalmers proposed that objects like notebooks or computers, when used in the right way, are as much a part of one’s cognitive process as the neurons in one’s brain. They portray this with the case of Otto, an Alzheimer’s patient who relies on a notebook to remember important information. Otto is benchmarked against Inga, who uses her biological memory. When Inga wants to go to a museum, she recalls the address from memory. When Otto wants to do the same, he looks it up in his notebook. Clark and Chalmers argue that the notebook is a constant, trusted resource for Otto, serving the same role memory serves for Inga, and thus can be considered part of Otto's mind. As they put it, "the notebook plays for Otto the same role that memory plays for Inga. The information in the notebook functions just like the information constituting an ordinary belief; it just happens that this information lies beyond the skin".

In Otto’s case, consulting his notebook isn’t fundamentally different from Inga consulting her brain since both are accessing stored information to guide their behavior. This example powerfully suggests that the mind is not limited to the brain. It can extend into the world via devices and tools, as long as they are integrated into our cognitive routines.

The question then becomes: at what point does an external tool count as part of you? Philosophers have offered several criteria sometimes called the “glue and trust” conditions for when we should treat something like a notebook or by extension, an app or AI as an extension of the mind.

Reliable Availability: The tool must be reliably present and readily accessible whenever you need it . (Otto always carries his notebook everywhere he goes.)

Ease of Use: Information from the tool should be easy to retrieve almost automatically, without great effort or delay. (In practice, using the tool becomes second-nature, like recalling a memory.)

Trust: You trust the tool and accept its outputs as true, much like you trust your own memory. (Otto doesn’t doubt his notebook; if it says “MoMA is on 53rd Street,” he believes it, just as Inga believes her recollection.)

Personal Integration (Prior Endorsement): Ideally, the information in the system was placed there or vetted by you, or in some way, you’ve integrated it into your identity. (Otto wrote the notebook entries himself, so they reflect knowledge he endorsed.)

When these conditions are met, the boundary between “tool” and “mind” gets fuzzy.

Clark and Chalmers explain that our everyday experience fullfills this. For example, a smartphone serves as a memory bank (with our notes, contacts, calendar), a navigation system, and even a “second brain” that we consult without a second thought. In fact, by 2011, even Chalmers noted that his iPhone satisfied at least three of the four criteria for a mind-extension device in skilled users’ hands. For many of us, losing our phone or internet connection feels like losing a part of our mind which is the extended mind thesis in action.

However, building an extended mind also comes with trade-offs and caveats. One obvious issue is that external tools can fail or be wrong. If any of the “glue and trust” conditions break down such as the device isn’t available, or you suddenly doubt its accuracy then the extension breaks down. For instance, experienced GPS users learn not to solely trust their GPS in all cases. They stay alert to correct it when it inevitably makes mistakes or loses signal. Only with skill and critical oversight can a GPS become a helpful extension of one’s navigational mind, rather than a mindless crutch. The same caution applies to AI assistants. Over-reliance on an external memory or skill can lead to cognitive atrophy where we might stop exercising our own memory or problem-solving abilities, becoming too dependent on the tool. Psychologists have observed this with phenomena like the “Google effect”, where people are more likely to forget information that they know they can just look up online. In other words, when a tool is always at hand, we offload mental work to it, which is great for efficiency, but might leave our natural abilities underdeveloped or prone to atrophy. There’s also the risk of false confidence, if the tool feels like part of your mind ,you might accept its outputs uncritically as if they were your own thoughts. With something like ChatGPT, as we’ll discuss, this is a double-edged sword as it can deliver brilliant insights, but also confident-sounding nonsense also known technically by AI researchers as hallucinations. An extended mind must therefore be built on trust and verification. We have to cultivate good “cognitive hygiene” and guardrails with our tools. It is important to know when to trust the AI and when to double-check, much as a good driver knows when to ignore a misleading GPS route. Abiding as a simple “left turn” could be deadly. The ideal is a balanced partnership where the external aid contributes knowledge or speed, and the human contributes oversight and contextual judgment.

ChatGPT as a Cognitive Extension

Alas the king… ChatGPT, the AI chatbot that launched in 2022, that is synonymous with the word AI itself. If any digital tool has the potential to act as a mind extension, ChatGPT is a prime candidate. It often satisfies the key conditions we listed.

Availability: If you have an internet connection, ChatGPT or similar models built into apps and devices is available 24/7, ready to answer questions or generate ideas on demand.

Ease of use: Absolutely, you just converse in plain language, and it responds within seconds. People have found it astonishingly easy to integrate ChatGPT into workflows by asking it to brainstorm topics, explain tricky concepts, draft emails, debug code, etc.

Trust: This is where it gets sticky; we’ll address its pitfalls soon, but many users do report that after some experience, they develop a sense of when to trust the AI’s answers for example, on a familiar topic or coding task and when to be cautious like when it confidently states an obscure “fact” that could be wrong. ChatGPT is often described as “having a super knowledgeable friend always at hand,” which indicates a high level of trust in the tools guidance.

Personal integration: Unlike Otto’s notebook, you didn’t personally write all of ChatGPT’s knowledge store – it comes pre-trained on vast swaths of the internet. However, you can customize the interaction by giving it your context, preferences, or writing style. Over time, the AI’s outputs might start to reflect your own way of thinking or the directions you nudge it toward, creating a kind of feedback loop between your mind and the AI. For example, ChatGPT’s Latent Memory feature makes that augmentation concrete. It quietly retains key details from past conversations, your projects, preferences, and stylistic quirks and uses them to shape future responses. As the model “gets to know” you, a slice of your working memory is effectively outsourced to the chat history, deepening the extended-mind partnership. In effect, when someone uses ChatGPT regularly, it can become a personalized cognitive aide, augmenting their natural abilities.

Empirically, we are already seeing how AI tools boost human cognitive performance. A recent experiment at MIT had hundreds of professionals work on writing tasks (emails, reports, etc.), with half given access to ChatGPT and half working solo. Those with ChatGPT finished their tasks 40% faster, and their output was rated ~18% higher in quality. In other words, the AI made people both quicker and better at their work. Interestingly, it was the weaker writers who benefited the most as ChatGPT helped close the skill gap between people, acting as an equalizer. This suggests that AI isn’t just a fancy convenience but rather can fundamentally alter someone’s cognitive productivity. In creative domains, anecdotal evidence shows AI sparking new ideas. Writers use ChatGPT to overcome writer’s block or generate plot ideas. Coders use it to learn new programming techniques on the fly. Students (unfortunately) use it to get instant explanations of complex topics. In many cases, people report that these tools help them achieve results they couldn’t have achieved (at least not as easily) on their own. For example, a non-programmer building a simple app with ChatGPT’s help, or a novice writer producing a polished essay by iterating with the AI. All of this aligns with the notion that ChatGPT can act as a cognitive amplifier. It extends what we know, effectively giving an individual access to a composite of Wikipedia, a librarian, a tutor, and a creative partner all at once. Little wonder that some have likened it to a “bicycle for the mind” (to borrow Steve Jobs’ old phrase for computers) except now the bicycle sometimes feels more like a jetpack. As AI copilots absorb the repetitive or low-level pieces of knowledge work, our top performers no longer rise by raw technical ability alone; they graduate from hands-on specialists to orchestrators. And in a world shifting from specialization to orchestration, these orchestrators hold the keys: they design the workflows, craft the prompts, select the data sources, and synchronize human talent with machine agents into a seamless whole unlocking outcomes no single expert could achieve in isolation.

The dawn of the orchestrator

Highway to the Danger Zone

That said, we must also address the drawbacks and dangers of relying on such AI extensions. Perhaps the biggest issue with current generative AI is that it can be too confident for its own good. ChatGPT doesn’t actually “know” facts in the way we do. It predicts plausible answers based on patterns in data. This means it sometimes produces fabrications that sound perfectly credible what we call “hallucinations” as described previously. For example, ChatGPT might cite studies or laws that don’t exist, or assert health facts that are utterly wrong but seem right. These inaccuracies are so common that researchers have given them a nickname and are actively studying why they occur. If a user treats ChatGPT’s output as gospel, trusting it like an infallible memory, they can get into trouble. A now-infamous case involved a lawyer who used ChatGPT to help write a legal brief, and the AI invented court cases to cite. The lawyer, assuming the AI’s confidently presented citations were real, submitted the brief and later faced professional sanctions when the judge discovered those cases were nonexistent. In this cautionary tale we can takaway that powerful cognitive extension can mislead you if you don’t remain critically engaged. Over-trust in the AI can lead to mistakes, misinformation, or the erosion of one’s own expertise. This is why many experts stress AI literacy and knowing the strengths and weaknesses of tools like ChatGPT as a crucial skill for the future.

Another consideration is how these tools fit into our broader cognitive habits. Do they complement our thinking or start to substitute for it? There’s a subtle but important difference between complementary and competitive cognitive aids. A complementary aid handles the tedious bits so that you can focus on higher-level thinking. For instance, using ChatGPT to perform basic data entry for you might free up time and mental energy for you to synthesize insights and make creative connections (things the AI might not do as well). In this mode, human and AI form a partnership where each does what it’s best at. By contrast, a competitive aid is one that essentially takes over a task that humans used to do, potentially sidelining the human role. If someone uses the AI in lieu of learning the basics or outsources all their creativity to an algorithm, they might be left with diminished skills and understanding. For example, if students lean on ChatGPT to do all their writing, they might never develop the ability to structure an argument themselves. The AI has “competed” with and supplanted their own cognitive growth. In the workplace, this distinction plays out as well: will AI assistants simply assist workers, or eventually replace those who don’t add unique value? Current evidence suggests that in many cases AI acts as a force multiplier for human talent , but we can’t ignore the possibility that some jobs or skills will be rendered obsolete. Navigating this will require conscious effort and we should embrace the complementary uses of ChatGPT that let us achieve more, while guarding against over-reliance that leaves us complacent or deskilled.

The Cyborg Question

All this talk of human-machine coupling naturally leads to the image of the cyborg. The archetypal transhuman figure who is part human, part machine. So, does using ChatGPT make you a cyborg? The answer depends on how we define cyborg.

Traditionally, the word means a “cybernetic organism,” implying a being with technology integrated into its body or biology. The term was originally coined in the 1960s to describe a person whose bodily functions are aided by implanted devices or biochemical modifications . Classic sci-fi cyborgs have robotic limbs, bionic eyes, brain implants, and so forth. By that strict definition, simply chatting with an AI on your phone doesn’t qualify. There’s no physical fusion of man and machine in the case of ChatGPT; the AI remains an external tool, not a literal part of your organic body. You could put your phone in a drawer and poof the “cyborg” abilities vanish, proving that you and the tool are separate entities. So, in the conventional sense, no, using ChatGPT does not make you a cyborg

.

However, some theorists have argued for a broader conception of cyborg-hood that applies to everyday life. Notably, anthropologist Amber Case argues that we are all cyborgs now in as much as we rely on technology constantly to extend our capabilities. You might not have a chip in your brain, but if you rarely go anywhere without your smartphone (your external memory/communication device) and you use digital tools to mediate so many experiences, you are functionally a cyborg. Case points out that we use our phones and computers like “external brains” for communication and memory, effectively becoming a “screen-staring, button-clicking new version of humans” . In this more metaphorical or sociological sense, anyone using ChatGPT as a cognitive crutch is engaging in a cyborg-like merging of human intellect with machine processing. The boundary between user and tool becomes porous during those moments of interaction. Think of how a person might say “I’ll ask my AI,” the way they’d say “I’ll think about it” – it hints that the AI has been incorporated into their cognitive loop. Some bioethicists and futurists use the term “soft cyborg” to describe people who, while not physically augmented, are so intertwined with their personal tech that it’s an extension of their self. By that view, millions of us became soft cyborgs the day we got smartphones, and tools like ChatGPT only deepen that intertwinement.

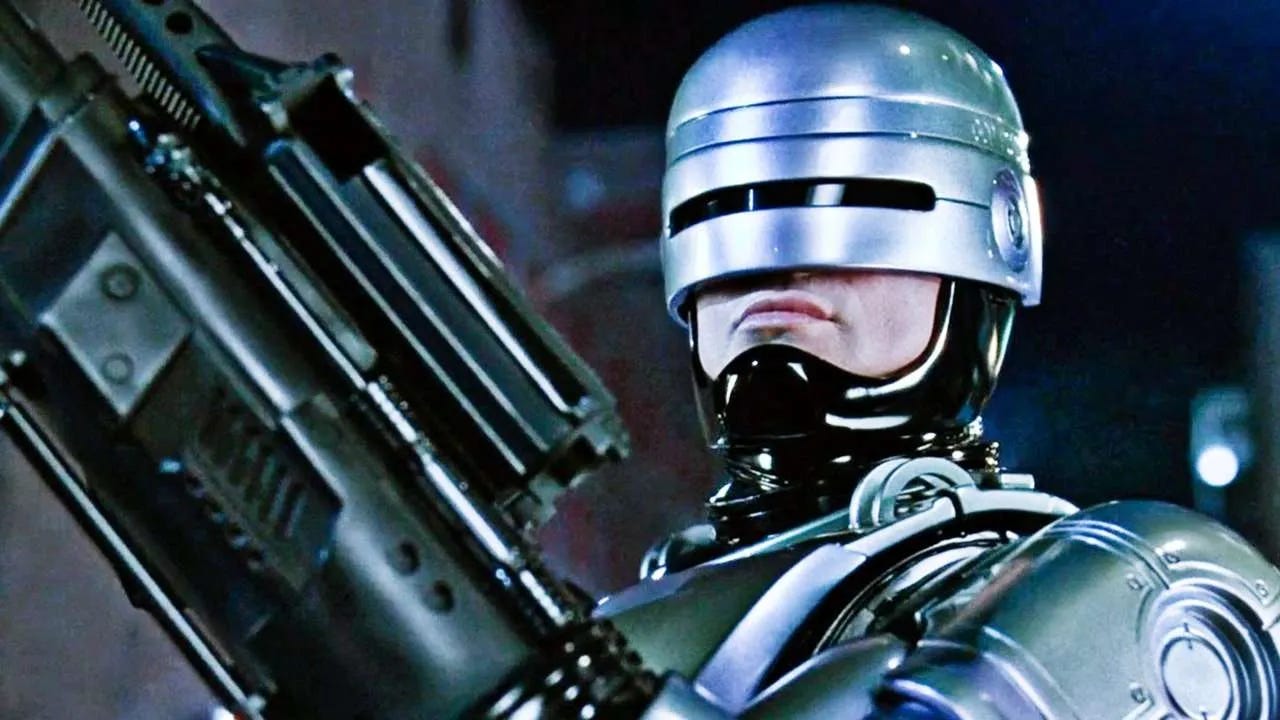

Even so, ChatGPT remains an external tool unless we literally implant it or physically couple it to our bodies. It’s worth clarifying where the line would be crossed into true cyborg territory. If, for example, in a decade we have a brain–computer interface (BCI) that lets you query an AI with your thoughts and receive answers as instant flashes of neural input, that would pretty clearly qualify as being a cyborg. Companies like Neuralink are already working on high-bandwidth BCIs that, in theory, could one day link human brains with AI systems. A less invasive route might be augmented reality glasses or contacts that overlay AI assistance onto your visual and auditory field at all times basically, an AI that’s always in your perception, not confined to an external screen. At that point, the AI starts to feel like part of your sensory system.

We can also imagine AI-driven neural prosthetics or implants that aids memory, or a language chip that provides real-time translation of foreign languages in your head. Those blur the line between user and device in a much more intimate way than a chatbot app does. ChatGPT, as amazing as it is, still lives in the cloud, you have to physically query it, and there’s a clear boundary (the interface, the screen) where information passes from machine to you. In cyborg terms, it’s one step short of full robocop.

So, calling ChatGPT users full “cyborgs” is mostly a playful metaphor hinting at the near future. A true cyborg enhancement becomes a part of you even when you’re not consciously thinking about it. One might argue like a pacemaker that keeps your heart rhythm steady, or a cochlear implant that continuously provides hearing.

In summary, using AI like ChatGPT moves us toward a cyborg-like existence in a philosophical sense, but it doesn’t make us cyborgs in the literal, physical sense. For that next leap, we’d need tighter integration at the physical level, at the current phase reliably consulting AI still largely requires skill.

The Haves and the Have-Nots: Access and Inequity in AI

If ChatGPT represents a sort of mass-market, over-the-counter cognitive enhancement, we should ask: Who gets to benefit from it? Historically, one concern in transhumanist technologies is that they might create a divide between the “enhanced” and “unenhanced”. For example, only the rich affording life-extending tech or brain boosts. With ChatGPT, the financial barrier is actually relatively low as the basic version has been offered free, but that doesn’t mean access is truly equal. First, there’s the straightforward digital divide: not everyone has a reliable internet connection or a modern device to use AI on. Billions of people still lack broadband access, and even within wealthy countries, underserved and rural communities may struggle with connectivity. Hardware and infrastructure are the baseline requirements for entry into this augmented world.

However, as observers note, a new divide is emerging that goes beyond just owning the tech – it’s about knowing how to use it effectively. Some have started calling this the AI literacy gap, akin to digital literacy but focused on understanding and working with AI. In other words, two people might both have internet access, but if one knows how to craft good prompts, interpret the AI’s output, and integrate it into their tasks, while the other is intimidated or unskilled with the AI, the first person will gain a significant advantage. We’re already seeing this in educational settings and workplaces. Students with strong guidance on using AI can produce better projects and learn faster, whereas those left unguided might either misuse the tool (e.g. simply plagiarize answers they don’t understand) or avoid it altogether out of fear. Similarly, a professional who adapts quickly to using AI tools may outshine colleagues who stick to older methods. This raises the concern that AI could exacerbate existing skill and socioeconomic gaps. Those who are digitally privileged having not just access but also the savvy to use technology can surge further ahead, while others lag behind.

Model Access

Another subtle access issue is the difference between the free versions of AI and the most advanced versions. For instance, OpenAI offers a paid subscription to ChatGPT Plus (with access to more powerful models like GPT-4). Organizations and individuals who can pay for premium AI will get significantly better results, more accurate, less hallucination-prone, with advanced features compared to those using only the free model. Over time, if cutting-edge AI remains behind paywalls, we could see a situation where wealthier users effectively have a “stronger cognitive enhancement” than others. This is not unlike healthcare disparities, except here it’s an intelligence tool. It’s easy to imagine a future where businesses invest in top-tier AI for their employees, training them in its use, and thereby dramatically increasing their output, while smaller firms or workers without such resources fall behind. However, as a hedge, open source models like deepseek have done the unthinkable with launching free models which could be run locally on a person's own computer. Though, enterprise grade hardware is required to run these full models to even spit out a simple question.

So, how do we address these gaps? AI literacy education is one key. Just as basic computer literacy became essential over the past few decades, knowing how to interact with AI should become a widely taught skill. This includes understanding AI’s limitations and ethical considerations, not just technical know-how. Initiatives are already calling for integrating AI training in schools and community programs. For example, learning how to fact-check AI or use it to assist (not replace) one’s learning could be built into the curriculum. Public libraries and online courses can play a role in democratizing knowledge about AI tools, so it’s not confined to tech specialists or elite institutions. Policymakers and organizations like UNESCO have begun discussing “AI literacy as a human right” in the digital age, emphasizing that without proactive measures, AI could deepen inequality rather than alleviate it.

On the infrastructure side, continuing to expand internet access is obviously crucial as every new person brought online is a potential new beneficiary of tools like ChatGPT. There’s also a case to be made for public interest AI: ensuring that advanced AI models are available in forms that the public and underprivileged communities can access perhaps via open-source models or government-provided AI services, rather than having all the best AI locked behind corporate gates.

In summary, ChatGPT offers a glimpse of a future where cognitive augmentation is widespread, but making that future equitable requires conscious effort. Otherwise, we risk a scenario where some minds get much “bigger” with AI help, while others are left behind in the pre-AI paradigm, widening the gulf in opportunity. The notion of transhumanism often dwells on individual enhancement, but we have to broaden that: true progress will be if these enhancements uplift as many people as possible, not just a tech-savvy few.

Conclusion: A Mind in the Making

We stand at a peculiar moment in human history. The tools we've created to extend our minds have become so powerful that they force us to reconsider what it means to be human in the first place. ChatGPT isn't just another productivity app; it's a mirror that reflects our evolving relationship with intelligence itself.

The central tension this essay has explored is not whether ChatGPT makes us transhuman (by most definitions, it doesn't), but rather what it reveals about the porous boundary between tool use and cognitive enhancement. When a technology integrates so seamlessly into our thinking processes that we struggle to separate our thoughts from its suggestions, we've crossed a threshold that demands new frameworks for understanding human capability.

Three critical tensions emerge from this analysis:

First, the enhancement paradox: ChatGPT simultaneously amplifies our abilities and threatens to atrophy them. We become more capable while risking dependence. The solution isn't to reject these tools but to develop new forms of cognitive hygiene: practices that maintain our intellectual muscle tone even as we delegate routine mental labor to AI.

Second, the equity challenge: Cognitive enhancement through AI could either democratize intelligence or create new hierarchies of the augmented versus unaugmented. The determining factor won't be the technology itself but how we structure access to it and, more importantly, education about its effective use. AI literacy may become as fundamental as traditional literacy, yet we're barely beginning to understand what that means.

Third, the agency question: As we transition from specialists to orchestrators, we must guard against becoming mere operators of intelligent systems. True agency in the age of AI means maintaining the ability to think independently, to question AI outputs, and to synthesize insights in uniquely human ways. We must be conductors, not just audience members, in the cognitive symphony.

Perhaps the most profound insight is that we've been augmenting ourselves all along: through writing, mathematics, computers, and smartphones. ChatGPT simply makes this augmentation impossible to ignore. It strips away the comfortable fiction that our tools are separate from our thinking and forces us to confront what we've always been: tool-using animals whose intelligence is distributed across our technologies.

The question isn't whether to embrace or resist this augmented future. It's already here. The question is how to shape it consciously. We need new ethical frameworks that account for distributed cognition, educational systems that teach orchestration alongside traditional skills, and a renewed commitment to human agency even as our tools grow more powerful.

In the end, ChatGPT offers us a preview of a future where the boundaries between human and artificial intelligence blur not through physical merger but through cognitive partnership. How we navigate this partnership with wisdom, equity, and intentionality will determine whether these tools amplify our humanity or diminish it. The choice, as always, remains ours.

References

Bajarin, T. (2014, April 21). Who needs a memory when we have Google? Time. https://time.com/69626/who-needs-a-memory-when-we-have-google

Bostrom, N. (1998). A history of transhumanist thought. https://nickbostrom.com/old/transhumanism

Bostrom, N. (2005). Transhumanist values. Ethical Issues for the Twenty-First Century, 3–14. https://nickbostrom.com/ethics/values.pdf

Brynjolfsson, E. (2022). The Turing trap: The promise & peril of human-like artificial intelligence. Daedalus, 151(2), 120–146. https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/publication/downloads/Daedalus_Sp22_19_Brynjolfsson.pdf

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. J. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19. https://www.consc.net/papers/extended.html

Clynes, M. E., & Kline, N. S. (1960, September). Cyborgs and space. Astronautics, 26–27. https://web.mit.edu/digitalapollo/Documents/Chapter1/cyborgs.pdf

Education Week. (2023, May 17). AI literacy, explained. https://www.edweek.org/technology/ai-literacy-explained/2023/05

Ghanem, K. (2025, May 9). Instagram face & BBL baddies—Welcome to the first wave of transhumanism. Mille World. https://www.milleworld.com/instagram-face-bbl-baddies-welcome-to-the-first-wave-of-transhumanism/

Hauser, C. (2023, May 27). Avianca lawsuit shows perils of citing A.I.-generated cases. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/27/nyregion/avianca-airline-lawsuit-chatgpt.html

IBM. (2023, September 1). What are AI hallucinations? https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/ai-hallucinations

Maiberg, E. (2025, February 10). Microsoft study finds AI makes human cognition “atrophied and unprepared.” 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/microsoft-study-finds-ai-makes-human-cognition-atrophied-and-unprepared-3/

Mentat. (n.d.). In Dune Wiki. Fandom. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://dune.fandom.com/wiki/Mentat

More, M. (1990). Transhumanism: Towards a futurist philosophy [White paper]. https://www.ildodopensiero.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/max-more-transhumanism-towards-a-futurist-philosophy.pdf

Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023, June 7). The productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence. VoxEU/CEPR. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/productivity-effects-generative-artificial-intelligence

OpenAI. (2024, February 13). Memory and new controls for ChatGPT. https://openai.com/index/memory-and-new-controls-for-chatgpt/

PhilPapers. (n.d.). Transhumanism. In PhilPapers. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://philpapers.org/browse/transhumanism

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776–778. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/dwegner/files/sparrow_et_al._2011.pdf

UNESCO. (2025, February 12). What you need to know about UNESCO’s new AI competency frameworks for students and teachers. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/what-you-need-know-about-unescos-new-ai-competency-frameworks-students-and-teachers

YouTube. (2025, February 15). Microsoft research discovers AI atrophies cognitive confidence [Video]. YouTube.

Really like this piece - excellent job, ser

GenAI as the clear accelerator of the human-mind, like proto-transhumanism. This is clearly the beginning of the path that companies like Neuralink are envisioning (and many in the transhumanism community have been envisioning for years).